The majority of musicians are familiar with a certain catalogue of scales, usually including major, minor, pentatonic, blues and dorian, as they are most commonly used in western music. However, there are countless scales available to us that are lesser known and should be explored to expand our overall knowledge and playing abilities. Examples include octatonic, enigmatic, harmonic major and the topic for today’s discussion: whole-tone, a scale that appears ever-expanding and consonant but dissonant at the same time. It has been used by 20th Century modernists composers such as Debussy and Satie but also popular icons like Stevie Wonder and The Beach Boys.

What is the whole-tone scale?

Put simply, it is a scale comprised entirely of whole step intervals. It can be thought of as the opposite to the chromatic scale. Because of this, it is hexatonic (6-note) and also symmetrical, meaning that it’s interval construction is the same ascending and descending, similar to that of dorian. Consequently, one interesting aspect of this scale is that there are only two: C whole-tone and Db whole-tone.

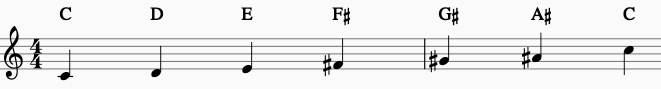

Scale 1: C whole-tone

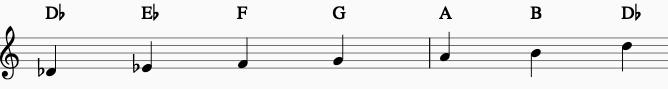

Scale 2: Db whole-tone

For example, let’s suppose we were to play E whole-tone, the resulting notes would be identical to that of scale 1 (E F# G# A# C D). Let’s suppose we were to play G whole-tone, the resulting notes would be identical to that of scale 2 (G A B C# D# F). Having just two scales to learn results in a fairly simple learning process.

After listening to the resultant sound of these scales, you will most likely notice two things. Firstly, the sound is like every flashback scene in any television show and secondly, there is very little sense of resolution; it almost sounds as if the scales are never-ending. The reason for this second thought is due to the absence of semitones, an interval that allows for resolution following dissonance. The reason a G7 – C (perfect) cadence sounds concluded is because the B resolves up a semitone to the C, and the F resolves down a semitone to the E. It is this sense of constant momentum that makes whole-tone particularly unique to work with.

Musical examples

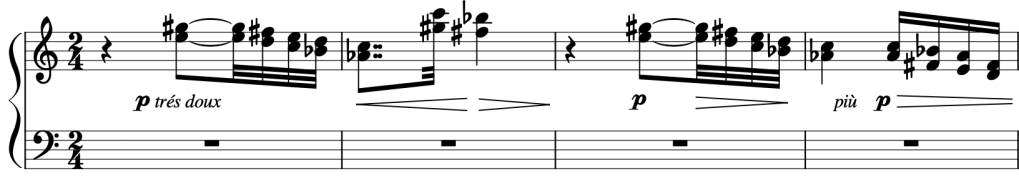

The most renowned musician to initially utilise the whole-tone scale was Claude Debussy (1862 – 1918), a modernist composer that constantly sought to break to the boundaries of musical language. In his 1909 piece Voiles, written for solo piano, Debussy explores the scale throughout, resulting in something that sounds eerily beautiful.

Have a look and a play-through the example below which notates the first four bars of the piece. All of the notes are found within C whole-tone. We can think of the key signature as being ‘open’ as there’s no direction towards a tonic.

Example 1: bars 1-4 of Voiles by Debussy

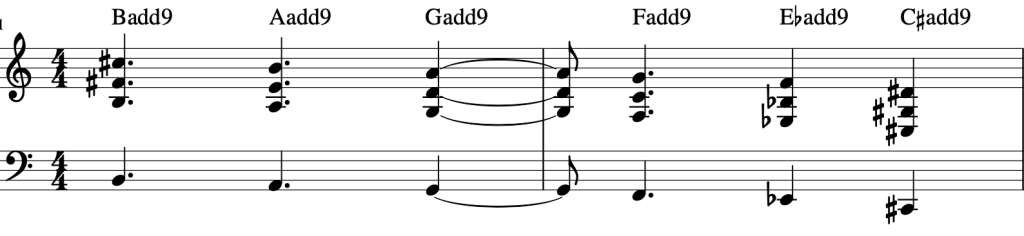

A more recent example of a musician utilising the scale is Stevie Wonder (b. 1950), a name that very few would be unfamiliar with. There are countless pieces where he explores it, but unlike Debussy, he demonstrates the sound in a more subtle way. In Contusion, a piece featured in his most recognised album (Songs In The Key Of Life), at around 40-seconds in, there is a clear demonstration of Db whole-tone. The notation in Example 2 highlights the harmony and specific voicings at this point. Despite the fact that not every note lives within the scale (such as the C in the Fadd9 chord), the root notes clearly descend down Db whole-tone and the chords being voiced as open fifths help produce a wonderfully ambiguous sound.

Example 2: Db whole-tone in Contusion by Stevie Wonder

Using the scale when improvising

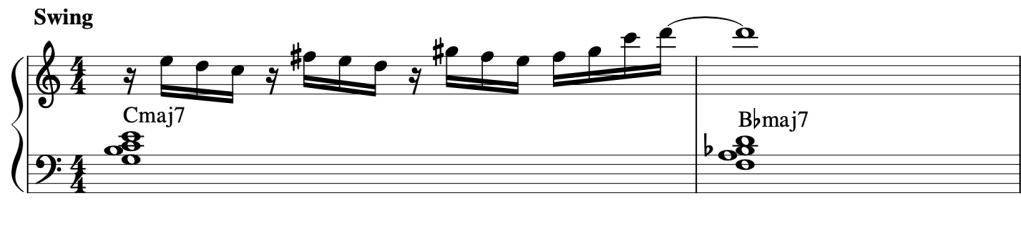

Having a scale like whole-tone in your back pocket can be very useful when you’re improvising as it will add some flair and unexpectedness to your playing. Examples 3 and 4 illustrate that whilst whole-tone is being applied, the resultant sound is beautiful but certainly ambiguous.

Example 3: C whole-tone over a Cmaj7

Example 4: G whole-tone over a G7

In both these licks the whole-tone scales produce #4s and #5s over the corresponding harmony, resulting in a bright sound that is yearning to settle in the next bar.

It is always beneficial to familiarise yourself with more unorthodox and complex scales, such as whole-tone, as you’ll firstly be able to recognise them when learning new pieces, resulting in a faster learning process, and secondly, you’ll be able to apply them to your improvisation, expanding your musical vocabulary. As with any unorthodox sound in music, make sure to tread with caution; an entire solo built solely on whole-tone may be up for criticism depending on the context of the piece. Some more exciting scales to explore are: octatonic, harmonic major and enigmatic.