Frédéric Chopin (1810 – 1849), a brilliant composer and pianist of the Romantic era, is someone that very few would be unfamiliar with. All of his compositions that we know of (roughly 230) involve piano, making his pieces desirable to learn for any pianist with an interest in classical music. Some of his most recognised works include Prelude in D flat major Op.15 No. 28, Nocturne in E flat major Op.9 No.2 and Larghetto from Piano Concerto No.2 in F minor Op.21. His pieces certainly range in difficulty, however one that is not considered to be simple is Fantaisie Impromptu, Op.66. Fantaisie Impromptu is something that all pianists seek to master, but many get stumped by its somewhat subtle complexities. This lesson brings these complexities to light and discusses strategies to tackle them, which will hopefully accelerate your learning process and improve your musical relationship with the piece.

The piece has a very clear structure of ABA (ternary) + coda and lasts a relatively modest 138 bars. The A sections are in C# minor and the B is in Db major. The movement from C# minor to Db major is described as a modulation to the parallel major, as C# and Db are of course the same note (enharmonic equivalents). First things first, make sure you are comfortable with these two scales as they are not the easiest to work your fingers around.

What makes this piece so challenging?

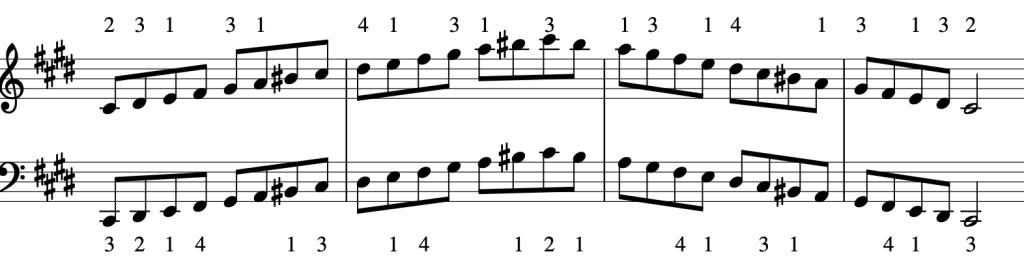

The main feature that causes Fantaisie Impromptu to be particularly difficult is the rhythm that overrides the A section. Have a look at the notation below that illustrates bar 5 of the piece.

You can see that the right hand is playing consistent 16th notes (semi-quavers) whilst the left hand is playing triplets (shown in groups of 6). This is the tricky rhythmic device that persists throughout both of the A sections and can be described as repeating 4:3 polyrhythms. Put simply, a polyrhythm is where you have two or more different rhythms occurring simultaneously. Splitting an individual bar into four quarter notes highlights four lots of 4:3 polyrhythms. Playing 16th notes or triplets on their own is not particularly challenging, but playing them simultaneously takes a great deal of concentration and practice, and the piece’s tempo marking of ‘Allegro agitato’ (roughly 160bpm) doesn’t make this task any simpler.

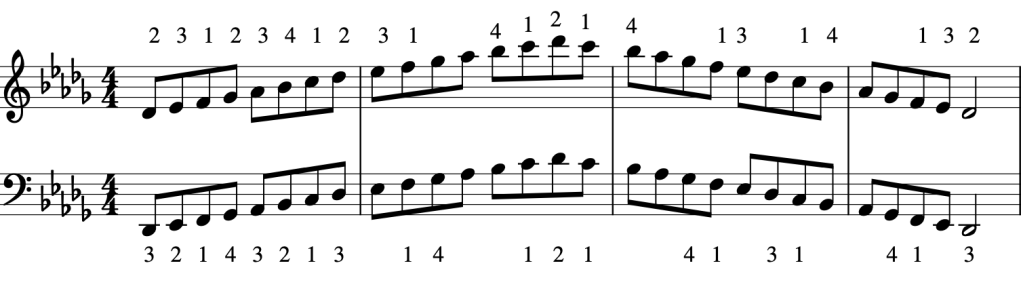

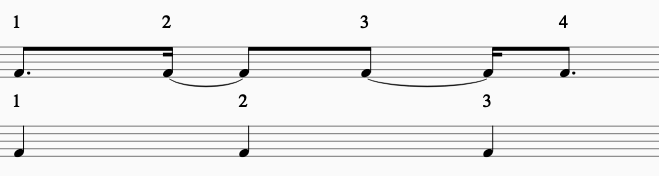

A great way to begin learning a polyrhythm like this is to not think of the 3’s and 4’s as separate, but to combine them into a one recognisable rhythm. Have a look at the notation below that shows what a 4:3 polyrhythm sounds like as one line.

Simply practice tapping this out with your hands, engraining the specific pattern into your memory. Once you’ve done this, you can then move onto separating your hands and executing the polyrhythm correctly. Again, you do not need a piano for this, just your hands and something to tap on.

You’ll notice that whether you’re working on exercise 1 or 2, the resultant pattern sounds identical. However, if you are struggling to memorising the rhythm, say the sentence “pass a bit of butter”. This nonsensical phrase sounds very close to a 4:3 polyrhythm and may help you remember it. Make sure not to underestimate the complexity of polyrhythms, they take time and patience to perfect, but it’s definitely worth investing some energy into them.

Once you become so comfortable with exercise 2 that you are practically dreaming about the rhythm, you can then move onto the piece itself and learn the necessary notes that make up the A section. Remember, the polyrhythm is just repeated over and over again. Although the tempo marking is fast, start practicing the piece at a slow tempo; perhaps half the necessary speed, then work your way up to around 160bpm. This is a point that cannot be emphasised enough as it will ensure you are firstly playing the right notes and working your hands around some tricky fingerings, and secondly that the rhythm is accurate. There is an unfortunate tendency to focus solely on the notes, encouraging the rhythm to become sloppy, but you must treat both rhythm and notes with equal importance.

What about the B section?

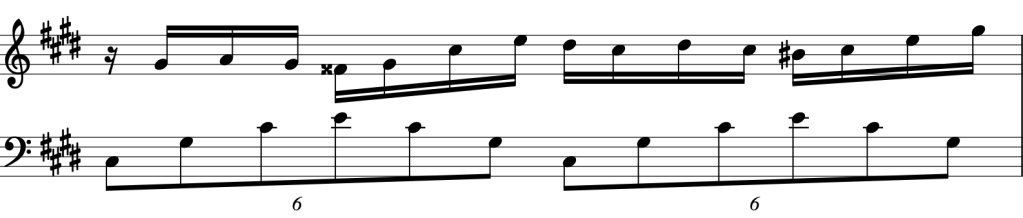

The learning of the B section should be substantially quicker. You are instructed to play this section slower (Moderato cantabile) than the A, and although the left-hand triplets are maintained, the constant 16th notes in the right hand disappears as the melody becomes more controlled and melodic. As emphasised by the marking ‘cantabile’, the right-hand melody should come through beautifully and you are free to add tempo changes in the form of rubato. Despite the B section being slightly easier to comprehend, make sure not to neglect it in the learning process as we need the whole piece to be accurate, producing the wonderful sound that Chopin intended.

As pianists, it’s great to attempt more complex pieces, improving our repertoire, and this short lesson emphasises that if you are struggling on a particular piece, break it down to its core essentials and work up from there. There is no use attempting Fantaisie Impromptu without first perfecting the 4:3 polyrhythm and similar strategies should be applied to any piece that is challenging you as a musician.