Ever catch yourself listening to music and thinking, “Wow, that chord sounded amazing”? I’d bet good money—well, at least 90% of the time (completely unscientific, of course)—that what you’re hearing is a secondary dominant. The dominant-to-tonic relationship has been the backbone of Western music since the 1600s, with its delicious mix of tension and release, and no other chord movement is as powerful or as widely used. In the UK, students are introduced to the dominant as early as Key Stage 3 (ages 11–14), but secondary dominants don’t usually appear until A-level (ages 16–18). To me, that’s a huge missed opportunity. The two ideas go hand in hand and can be taught together from the start—something I make sure to do with all my students, no matter their level, adjusting the complexity as needed, of course.

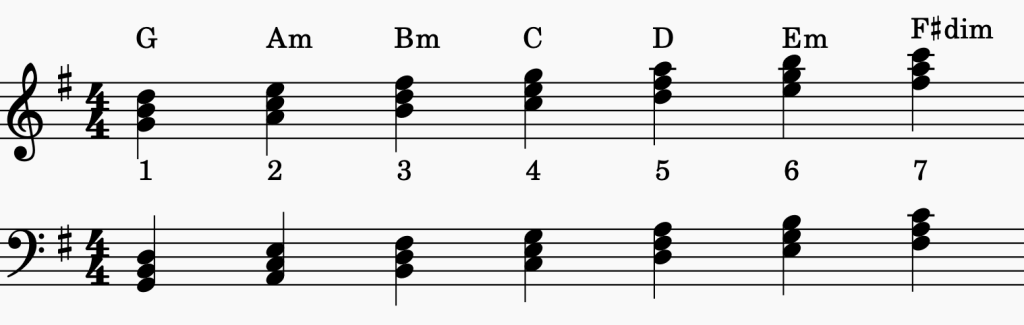

Let’s start with a dominant chord. In every key, we have a selection chords that ‘exist’ within it. For example, here are the chords in the key of G major:

These are the basic triads (3-note chords) that are built on each note of the scale.

The 1st chord (G major) is known as the tonic.

The 5th chord (D major) is known as the dominant.

A movement from the 5th chord to the 1st chord is our dominant-to-tonic, or perfect cadence, or V-I (if we feel like a fancy Roman).

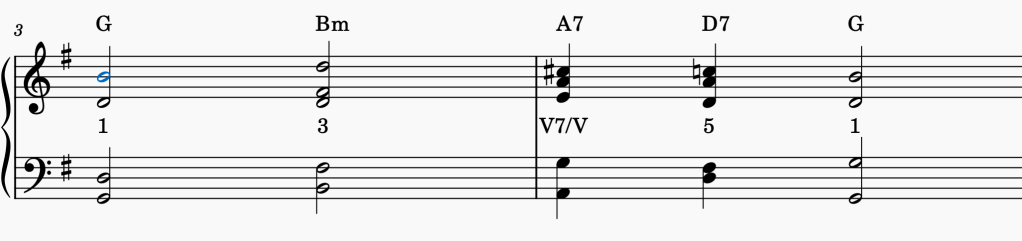

Here’s a simple chord progression in the key of G major:

The movement between the C and D7 chords is our dominant-to-tonic. To add additional dissonance, sweetening the resolution, the 5 chord is turned into a dominant 7 (this is optional but common practice).

A secondary dominant, therefore, is a chord that temporarily acts as the dominant of a chord other than the tonic. This device creates momentary tonicizations (brief suggestions of a new key) without fully modulating (officially changing key).

Here’s a chord progression that uses a common secondary dominant: V7 of V (I will explain the name momentarily).

The first thing you’ll notice is the A7 chord, which does not belong in the key of G major. But it does exist in the key of D major—and as you can probably guess, A is the fifth chord in D major! What we’re doing here is using the V7 chord of D major (A7) to lead us toward D (V in G major). This is why it’s called a V7 of V. We’re writing this as roman numerals as this is the common tradition, but you can say it as ‘5 (7) of 5’

The A7 chord is therefore described as a secondary dominant, with its role to create a strong pull towards D major, giving the sense of a temporary tonicization, all without actually leaving the key of G major.

The beauty is that secondary dominants can be used anywhere in a progression, pushing you towards any chord.

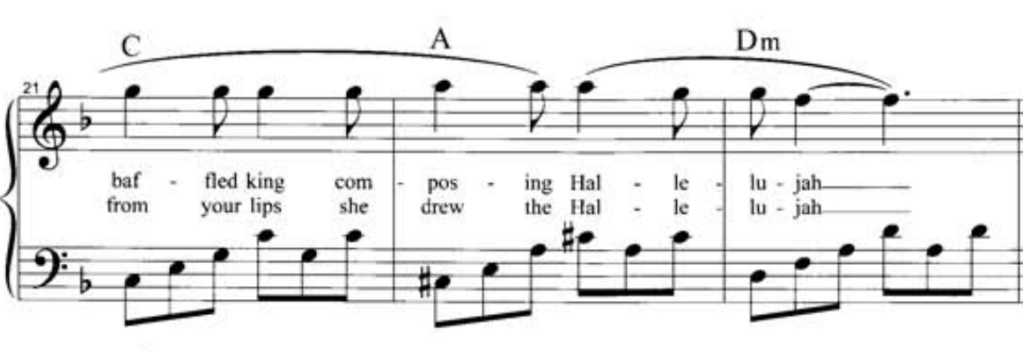

One of my favourites is the V7 of vi (‘5 (7) of 6’). In the key of C major, this is the movement from E7 to A minor. This secondary dominant is particularly

beautiful and adds an immensely emotive moment to any piece.

Here are some incredible examples of the V7 of vi being used in well-known pop songs:

Hallelujah by Leonard Cohen (key: F major) – The A (V7/vi) to Dm (vi) movement.

She’s Always a Woman by Billy Joel (key: Eb major) – The G (V7/vi) to Cm (vi) movement.

So often when people listen to these pieces, they pinpoint these exact moments and describe them as deeply emotive and simply beautiful.

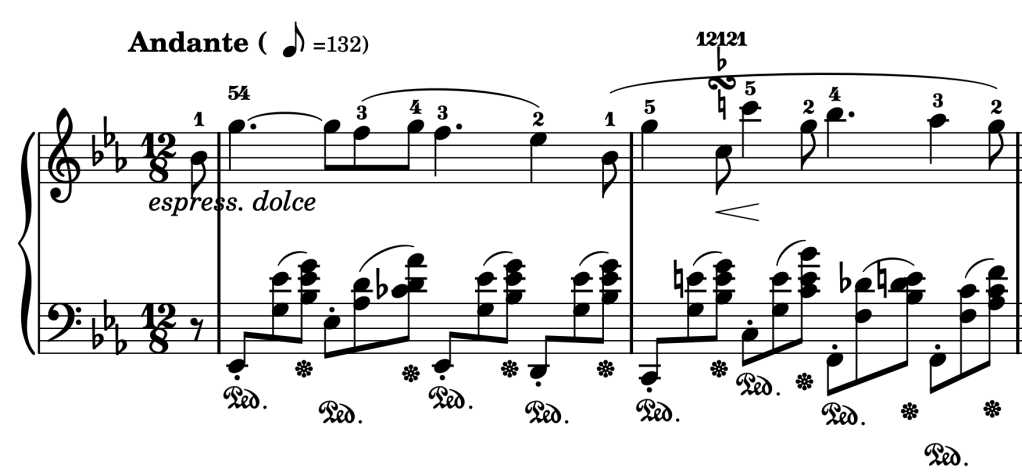

And if you thought the secondary dominant was isolated to one particular genre or era you would be mistaken. The secondary dominant has been utilised since the establishment of the dominant-tonic relationship in the Early Baroque period (1600s), with composers like Monteverdi and Corelli. This carried on into the Main Baroque period (1700s) with composers like Bach and Handel and by now, they were codified enough that theorists recognised them as essential tools of tonal harmony. By the Classical period, secondary dominants had become routine structural devices. You’ll struggle to find a piece by Mozart that doesn’t have one. In the Romantic period, composers like Chopin and Liszt exploited them as part of continuous harmonic motion, often blurring the sense of a single tonic. And of course, the tool carried straight through into the 20th century being utilised constantly in Jazz, Pop, Film Music and any other genre you can think of. On that note, here’s some more examples across all eras and styles of music:

Nocturne Op.9 No.2 by Chopin (key: Eb major) – Bar 2, movement from C7 (V7 of ii) to Fm (ii).

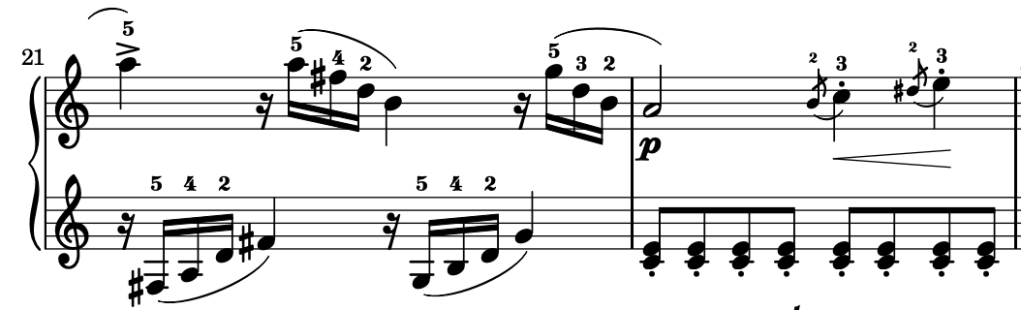

Sonata in C Major by Mozart (key: C major) – Bar 21, movement from D7 (V7 of V) to G (V).

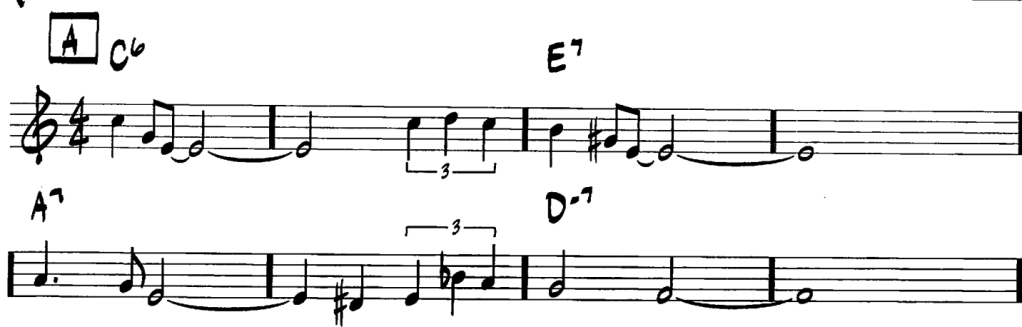

All of Me by Simons and Marks (key: C major) – Bars 3-7, a train of secondary dominants. E7 (V7/vi) takes us to vi played as A7 (V7/ii) which takes us to ii (Dm7).

Whether you’re a performer, composer or student I implore you to embed this topic into your mind for the rest of your musical life. Secondary dominants are essential to musical composition and having a deeper understanding of them will not only allow you to utilise them in your writing and improvisation but also to hear them and experience them in your everyday listening. What a beautiful thing.